Across the stories in “Burning Chrome,” neural implants appear with remarkable consistency. Johnny Mnemonic stores encrypted data in his brain. Characters throughout the collection have ocular modifications, neural interfaces, exoskeletal augmentations. Gibson’s future is one where body modification for technological integration is ubiquitous, assumed, barely remarked upon. In 2026, this hasn’t happened.

L’Ubiquità degli Impianti come Scelta Stilistica

The interesting question isn’t whether Gibson accurately predicted technology—most SF doesn’t. It’s why he chose neural implants as his primary technological motif, and what function they serve in the narrative architecture. One possibility: they’re a shorthand for intimacy with technology, a way to make the relationship between human and machine visceral rather than abstract.

When Johnny Mnemonic carries data in his brain, the stakes become biological. The information isn’t on a device he can discard; it’s inside him, threatening his cognitive function if he can’t extract it in time. The technology becomes body horror, which creates dramatic tension more effectively than, say, a character carrying a encrypted hard drive in their pocket. Gibson needs the technology to be invasive to make it matter narratively.

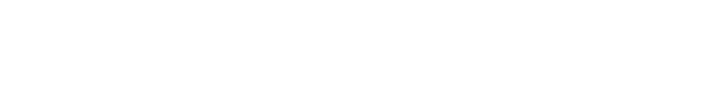

Il Divario tra Predizione e Realtà

What actually happened: technology got smaller, more portable, more integrated into daily life—but not into bodies. Smartphones, wearables, ubiquitous connectivity, but external. The closest we’ve come to Gibson’s vision is Neuralink, and even that remains experimental, focused on medical applications rather than consumer augmentation. The expected trajectory—toward invasive modification—didn’t materialize.

Why? The transcript offers one explanation: “the human body is naturally resistant to that.” This gets at something Gibson may have underestimated: biological conservatism, immune system rejection, the simple fact that bodies don’t want foreign objects inside them. Surgery has risks, infections happen, implants fail. Meanwhile, external devices improved fast enough that the value proposition for invasive modification never became compelling.

La Funzione Narrativa vs. Plausibilità Tecnologica

If neural implants don’t work as prediction, what function do they serve? They might be Gibson’s equivalent of faster-than-light travel in space opera—a narrative convenience that enables certain kinds of stories. FTL lets you have galactic empires and space battles. Neural implants let you have technology that characters can’t escape, that’s part of their identity rather than their toolkit.

This distinction matters for understanding what kind of futurism Gibson was practicing. He wasn’t trying to forecast the specific path of technological development. He was identifying a relationship—the increasing intimacy between human cognition and digital systems—and literalizing it through body modification. The implants are a metaphor made physical, a way to explore psychological and social dynamics that might have happened even if the specific technology didn’t.

Cyberspace come Alternativa alla Modificazione Fisica

Interestingly, Gibson’s other major innovation—cyberspace—had more predictive success. Not the neon-lit geometric space he described, but the concept of a parallel digital environment where identity and action take place. The internet happened. Virtual worlds happened. People do spend significant portions of their lives in digital spaces that feel psychologically real even though they’re accessed through screens rather than neural jacks.

This suggests that Gibson’s instinct about the human-technology relationship was sound, but his assumption about the interface was wrong. We didn’t need to modify our bodies to achieve intimacy with digital systems. We just needed the systems to become responsive enough, immersive enough, that using them felt natural. An iPhone is less invasive than a neural implant, but it’s arguably more integrated into daily consciousness for most users.

La Resistenza Biologica come Limite Narrativo

The transcript mentions that “animal bodies are resistant to a lot of things”—breeding in captivity, excessive cultural pressure, invasive modification. This might be the core insight Gibson missed. Bodies have their own logic, their own constraints, that don’t necessarily align with technological possibility. Just because you can implant something doesn’t mean the body will tolerate it long-term, or that users will choose it over less invasive alternatives.

Science fiction often underestimates biological conservatism because it’s less dramatic than technological possibility. A story about characters gradually becoming more dependent on external devices is harder to make visceral than a story about characters with computers in their skulls. Gibson chose drama over plausibility, which is a defensible artistic choice. It just means his work functions better as psychological exploration than technological forecasting.

The question that remains: if the intimacy between human and digital has increased as Gibson anticipated, but through different mechanisms than he predicted, what does that suggest about the next thirty years? Will external devices continue to improve faster than invasive alternatives can overcome biological resistance? Or will there be a threshold where the advantages of direct neural interface finally outweigh the costs and risks?