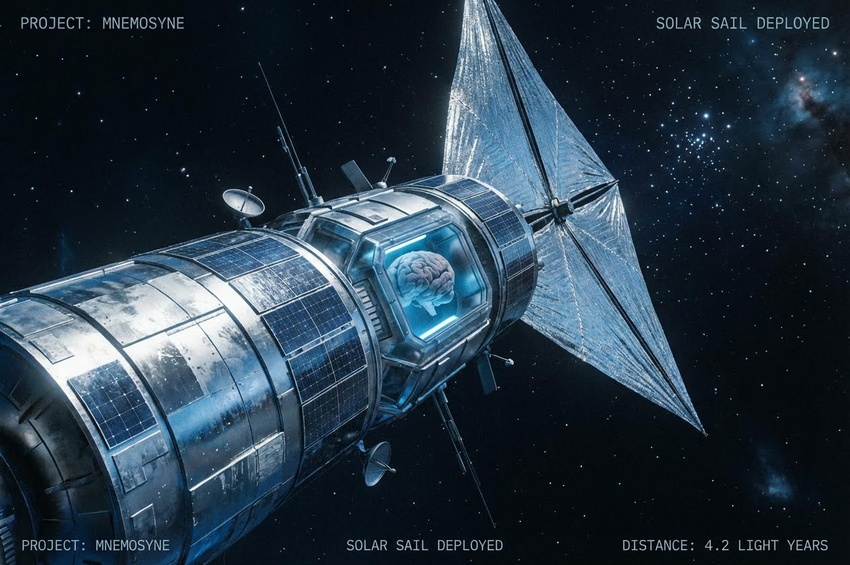

“The Gernsback Continuum” operates on an unusual premise for a Gibson story: it’s not about the future, but about failed predictions of the future. A photographer is commissioned to document “the Eighties that never was”—the streamlined, chrome-plated, rocket-ship future imagined by mid-century designers and never realized. The story’s central observation comes early: “What the public wanted was the future.”

La Distinzione tra Futuro Venduto e Futuro Realizzato

Gibson draws a line between two types of futurism. One prioritizes aesthetics, inspiration, the aspirational image of what could be. The other prioritizes accuracy, plausibility, what will actually happen. The distinction matters because mid-century futurism—the Gernsback aesthetic referenced in the title—fell almost entirely into the first category. Streamlined cars, atomic-powered everything, cities of tomorrow with moving sidewalks and glass towers.

None of it happened, at least not in the form imagined. Yet the images persisted, became cultural touchstones, shaped how generations thought about progress. Gibson seems interested in this gap—the space between what was sold and what arrived. The photographer protagonist sees these futures as “semiotic ghosts,” images that haunt the cultural imagination despite being divorced from material reality.

La Fotografia come Testimone Problematico

The story uses photography as a structural device. The protagonist’s job is to capture these retro-futures, to document their aesthetic. But photography is an ambiguous medium—it records what’s there, but it also frames, selects, interprets. When the photographer begins seeing UFOs, Art Deco futures manifesting as hallucinations, the story asks: what’s the difference between documenting a defunct aesthetic and being possessed by it?

His solution comes from another character: “Really bad media can exorcise your semiotic ghosts.” The idea being that consuming enough low-quality, mass-produced content can overwrite the powerful aesthetic visions lodged in consciousness. It’s a fascinating inversion of the usual relationship between “high” and “low” culture—here, trash media serves as a kind of cognitive reset, breaking the spell of beautiful but false futures.

Il Futurismo come Possessione

Gibson treats the Gernsback aesthetic almost like a virus or entity. The photographer doesn’t just remember these images; he starts experiencing them as intrusive visions. They interrupt his perception of reality. The story suggests that sufficiently powerful aesthetic visions can function as alternative realities, competing with the actual world for cognitive space.

This has implications for how science fiction functions. If SF is meant to predict the future, it fails most of the time—rocket ships to the moon, yes, but not atomic cars or food pills. But if SF is meant to sell a version of the future, to make it desirable or thinkable, it succeeds even when the predictions fail. The Gernsback aesthetic didn’t accurately forecast the 1980s, but it did shape how people thought about technology, progress, the relationship between design and tomorrow.

Il Problema della Precisione vs. Ispirazione

Gibson wrote “Burning Chrome” in the early 1980s, right around the time he was developing the cyberpunk aesthetic. He was explicitly trying to move away from the Gernsback model—away from shiny futures and toward gritty, plausible, near-term extrapolation. Yet “The Gernsback Continuum” suggests he understood the appeal of the older model, the power of selling a future even if it’s not accurate.

There’s a tension here that runs through all of Gibson’s work. He wants to predict plausibly—neural implants, cyberspace, corporate dominance—but he also wants to create a compelling aesthetic, a vision readers can inhabit. Sometimes those goals align. Sometimes they don’t. When they don’t, which one wins?

The story doesn’t answer this directly, but the photographer’s arc suggests something. He’s commissioned to document a dead future, ends up haunted by it, and escapes by consuming garbage media. The implication might be that taking these aesthetic visions too seriously—treating them as real or achievable—leads to a kind of madness. Better to enjoy them, use them, but recognize them as constructs rather than prophecies.

What happens when a generation grows up expecting the Gernsback future and gets something completely different? Do the semiotic ghosts persist, creating permanent dissatisfaction with the world as it is?